It’s no secret on this blog just how much I adore, I repeat, adore, the story of The Nutcracker. Seeing the ballet live onstage has become a holiday staple for me, and my memories of it go way, way back. My first exposure to the story was seeing a live Disney show where Mickey Mouse and his friends reenacted the story, and the story was included in a collection of Christmas stories my grandparents gave me and my sisters.

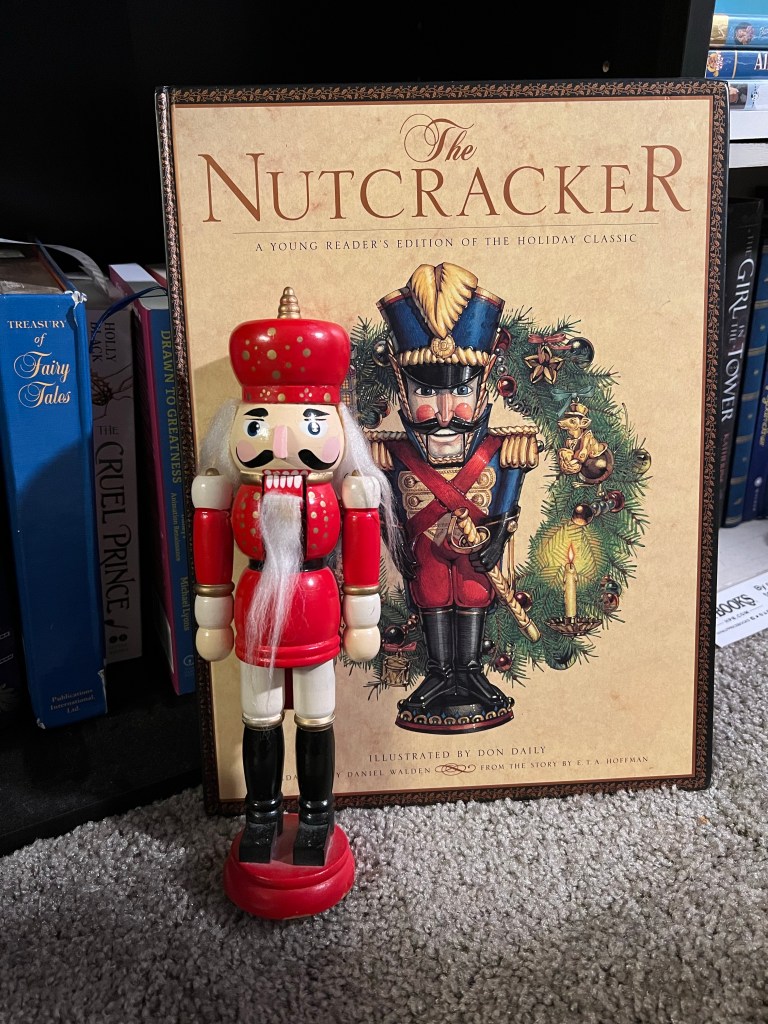

When I was seven years old, I received a gift set for Christmas that included a huge picture book of the story and a wooden nutcracker toy. I played with that nutcracker so much that my dad had to super-glue his arm, his beard, and his hat back into place. To this day, that picture book, whose illustrations captivated me so much, still sits in my library and the nutcracker goes back on display every holiday season.

I was so in love with the story inside that picture book that I would reenact it, putting on my Samantha Parkington nightgown and dancing with my nutcracker in my arms, pretending to be Maria. And when Barbie in the Nutcracker came out, you can bet I asked my mom to buy me the DVD and all the accompanying dolls. I think it was even this story that kick-started my deep love for stories about toys coming to life and taking their owners on magical adventures.

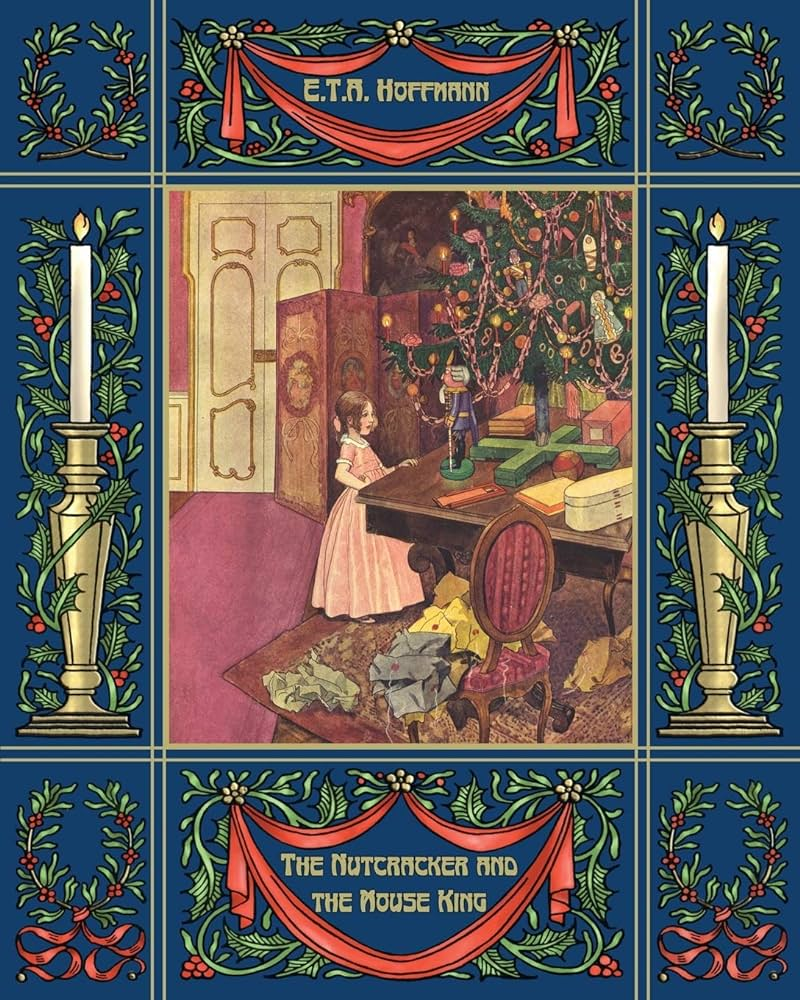

For all the Nutcracker stories I’ve reviewed here, I’ve never talked about the E.T.A. Hoffmann story that inspired the ballet and the Alexandre Dumas novel retelling. So let’s put on our ballet slippers or soldier hats and dance into the story, shall we?

On Christmas Eve, young Maria Stahlbaum and her siblings Fritz and Louise attend their family’s Christmas festivities. Among the gifts is a wooden nutcracker toy, brought to the party by the children’s godfather Drosselmeyer. Despite his strange appearance, Maria immediately falls in love with the nutcracker, and looks after him after Fritz cracks the toy’s jaw on a hard nut. In the meantime, Drosselmeyer tells Maria and Fritz the story of how the nutcracker came to be who he is, kick-starting a fantastical adventure that tests Maria’s bravery and love as she sets out to restore the nutcracker to his original form.

For many people, this is the Christmas fairy tale, and this version certainly reads like one. Hoffmann addresses the reader several times throughout, asking them to imagine certain scenarios to better understand what Maria and the Nutcracker go through. You could probably read this version out loud next to a fireplace, surrounded by attentive readers, and the effect would be quite warm and magical.

And of course, there is the story-within-the-story, where Drosselmeyer tells Maria and Fritz about Princess Pirlipat and the Hard Nut. Since Princess Pirlipat’s story does not feature in many adaptations, I was surprised to learn of its existence, but it does add another fairy tale layer to the story. Imagine the story of Beauty and the Beast, but now with a princess becoming a beast and a handsome young man coming to her rescue, and it’s cracking open a hard nut that breaks the spell instead of true love.

Fairy tales can have some strange arbitrary rules for causing or breaking curses, and the Tale of the Hard Nut has some of the most ridiculous of all. To restore Princess Pirlipat’s beauty, a young man not only has to crack open the Hard Nut, but he also has to walk backwards seven steps without stumbling, has to have never been shaved, and can never have worn boots. You wonder how many sets of broken teeth it took to figure out those rules.

Surprisingly, this story takes up a good chunk of the text. Another thirty to forty percent goes into describing the two battles with the Mouse King, who, unlike most adaptations, has seven heads. Each battle goes on a little longer than necessary, I think, with a few too many diversions between how each toy is faring. Even as a kid, the battle scene was never my favorite part. I think it’s usually because Maria plays a very small part in it, until the iconic moment when she throws her slipper at the Mouse King. I always wanted her to jump in and help out, and not hide like a damsel on the couch. Yes, she is a little girl, but her beloved nutcracker needs her; surely she could work up the courage to do something more than just throw a slipper.

Something else that shocked me was how underwhelming the Land of Sweets was. I think it had much to do with the rinse-and-repeat nature of it: Maria sees something, does a lot of ooh-ing and ahh-ing, and the Nutcracker tells her the name of it. Sure the concept is cute and enchanting, but I don’t think Maria needed every little thing pointed out to her.

The same kind of went for when they get to the Capital and the different dancers come out. Maria questions what they are, and the Nutcracker has a long explanation for each one. So rather than watching the dancers themselves, we get to listen to Nutcracker exposit about them all. Suppose that’s one more leg up for the ballet.

Maybe I’m missing something, but the ending had me a little confused.

When Maria wakes up from her journey into the Capital, she meets Drosselmeyer’s nephew, who is also her nutcracker. Out of gratitude for her saving him, he asks her to come away to the Land of Sweets to be his bride, which she does a year after he proposed to her.

Remember that Maria is supposed to be seven years old. A seven-year-old is asked by a young teenager (because also remember that he never should have shaved in order to break Pirlipat’s spell) to marry him.

I truly wonder about the truth of that ending, since not even in the nineteenth century would a teenage boy make an earnest marriage proposal to a seven-year-old.

Am I reading too much into the ending of a children’s fantasy story where this is not the only thing that doesn’t make sense? Perhaps. But still, a little clarity would be welcome.

So it sounds like I’m quick to praise the ballet to no end, but the story itself is a mess, right? Well, I like to think of the Hoffman story as more of a draft of the story. Some things didn’t make sense in it, so they were either taken out or cleaned up a bit for the ballet to happen. I mean, it’s not the first time where the original material was kind of a mess, but got a much cleaner, more entertaining adaptation in another medium.

Despite its narrative flaws, I do still like this version of The Nutcracker. Do I think it’s superior to the ballet? Nope. Will I still come back to it from time to time when I want to read a Christmas fairy tale? Sure, but I’ll more likely turn on the ballet music or watch one of many performances available online.