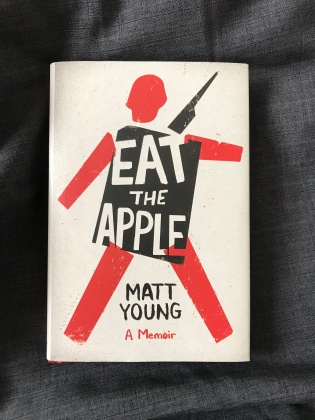

Several months back, I proofread a rather in-depth and informative interview between the Editor-in-Chief of Split Lip and Matt Young, who had just written an Iraq war memoir called Eat the Apple. Imagine my surprise and delight when said Editor-in-Chief announced that Matt would be coming on board as our Memoir Editor! I learned a lot from his interview, not just about the making of Eat the Apple, but also about craft and composition and teaching—something he has provided further assistance with since joining the Split Lip team. So I hope this review serves as an adequate thank-you for all his advice.

I know little about war. At least I know little about the reality of it. Sure, I studied wars for my college history minor, but memorizing the deaths, the dates, and who ultimately won, is not the same as having seen firsthand the blood, the despair, and the numbness of combat. You don’t talk about war in the same conversation as neighborhood gossip or grocery lists, so when someone pulls back the velvet curtain, you can’t expect to see a pageant of heroism and sure victory.

I expected this book to be good, as I judged from Matt’s interview. But I didn’t expect it to make me consider the adage I hold closest to me: that joy and love will always triumph. Even as I write this, I keep pausing to think that sometimes, it is not our joys and hopes that tie us together, but our fear and despair. Life beats us down time and time again, and we all have burdens to bear, and sometimes, the only joy we can find is the fact that we are not the only ones who are afraid, or angry, or despairing. That was a profound enough moment where I put the book down, stared out the window at the snow, and cried a little.

It also made me consider just how much we romanticize war—how much we romanticize a lot of things. In the way that we make jumping rope songs out of the Black Death, the same way we insist that the end justifies the means in war. I still think that it takes much gumption and guts to enlist, but there is still nothing glorious about death and blood, nor the psychological and physical hardships needed to survive a war. And yet, we put a polished, Hollywood-epic scrim over it because it is the only way we can process something so horrible. It’s one thing to put a scrim over our small, daily woes, but to put it over something where entire nations fall and people lose themselves to protect against such horrors…

I think that is why we have such a hard time talking about war, because we don’t know how to reconcile what we think it is like with what non-heroic things must actually be done in the name of it. People often mean well when they say “Thank you for your service,” but the buffed-up reasons for fighting (the American values of independence and freedom and strength of will) don’t meet with what actually happens (death, the indifference created toward it as a defense mechanism, psychological and physical trauma, etc.).

That being said…

Matt’s voice is blunt, and at times sweeping. The language either cuts right to the point, or it takes you on a driven tangent that leaves you in breathless tears by the end. This book also has pictures and diagrams. This way, Matt doesn’t have to describe how to make a raft, or some clever desire-satiating gizmo made of towels, rubber bands, and a rubber glove: helpful drawings of each shows you how it’s done instead. Although the subject matter is heavy, self-deprecating humor is still sprinkled throughout, which doesn’t do much to soften the topic, but makes it just a little more palatable.

Eat the Apple has set a high bar for other war memoirs to leap over, because it doesn’t wax romantic about anything, and it makes you think. I don’t normally talk about endings, but this one is a fine example, and doesn’t spoil other stories before it. The final essay is a single-question survey about how one feels after returning from combat, with possible answers ranging from “Outstanding” to “Not too bad. I can’t complain, I guess.” Till the end, the book refuses to soften anything, and that ending—neither happy nor sad—couldn’t have been more perfect.